‘Two Households, Unalike in Dignity’: The Politics of Shame and Architectural Transformation in Salem, Massachusetts (1660-1730)

- TJ Moss

- Sep 27, 2024

- 14 min read

Autumn always brings about a reinvigorated interest in New England. From consuming media set in the Northeastern subsect of North America to traveling to see the fall foliage, people love to gawk at the changing landscape vibrantly colored in red, orange, and yellow. Seemingly, the pinnacle of the autumnal season can be spent looking back to the colonial past. The nostalgia for warmly lit spaces and comforting furniture sets the scene for the idealization of colonial and colonial revivalism in art, design, and other forms of media. The beauty of New England is constitutive within the nostalgic renderings inherent in the media associated with the area. Overlooking the lighthouses, covered bridges, and colonial architecture, one can see the bewitching effect of the built environment. However, the mythologies associated with the American Northeast are only veiling imperialism, religious intolerance, and consternation. Even little houses on seemingly sweet streets hold dubious histories. Looking toward the metanarrative within the architecture of the Johnathan Corwin House, also known as the Witch House (c. 1675) and the Ropes Mansion (c. 1727) in Salem, Massachusetts, we will see how design displays the mythologies that temper our fears.

Georges Inness (American, 1825-1894) Autumn Oaks (1878) Oil on Canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Arthur Miller's (1915-2005) 1953 play, The Crucible, is about the Salem Witch Trials (1692) and lives in the public consciousness due to its ubiquity in the American school system curriculum. The story transcends itself as a parable for the concurrent McCarthyism and bridges the gap between the literature of the New World, American Gothicism, and the 20th century. However, the play does much more than tell the historical accounts of late seventeenth-century New England. Delving into the story of the Salem Witch Trials enables the reader to critically engage with and understand the complexities of mass paranoia, abuse of power, and ideology.

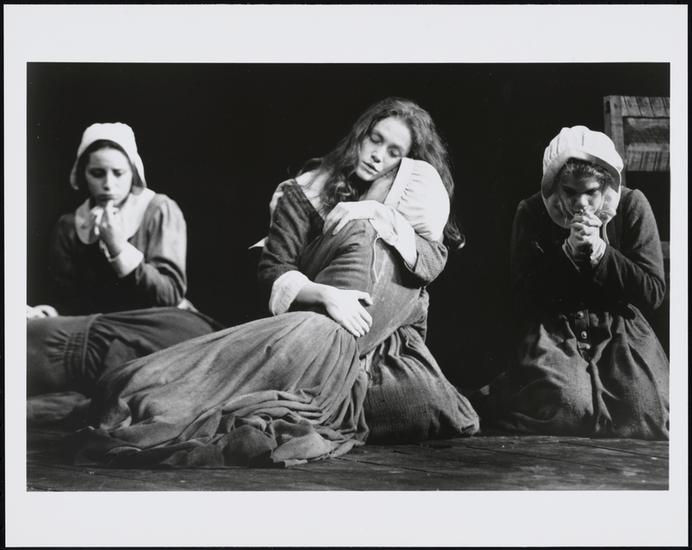

Unknown Photographer. The Crucible Theatre Still (1953). Gelatin Silver Print. Museum of the City of New York.

At its core, the play is about unrequited love, focusing on teenage Abigail Williams and thirty-year-old John Proctor. Both characters are stolen from history books, but certain liberties have been taken to dramatize the points further. After an affair with Williams, Proctor wishes to repair his marriage to his wife, Elizabeth. At the beginning of the play, Reverend Parris comes across Abigail Williams, Mercy Lewis, Betty Parris, Ruth Putnam, and Mary Warren dancing in the forest with an enslaved Indigenous woman, Tituba. Theories of demonic possessions and preternatural experiences within the small town begin to circulate after Betty, Reverend Parris' daughter, is found collapsing in and out of consciousness. In hopes of not getting in trouble and reviving a romance with Proctor, Williams and other girls in the town start accusing people of witchcraft.

William Auerbach-Levy (American, born Belarus 1889-1964)[Arthur Kennedy as John Proctor, Beatrice Straight as Elizabeth Proctor, and Walter Hampden as Deputy-Governor Danforth in "The Crucible".] (1953). Drawing.

William Auerbach-Levy (American, born Belarus 1889-1964)[Ford Rainey as Deputy Governor Danforth, Michael Higgins as John Proctor and Barbara Barrie as Elizabeth Proctor in "The Crucible".] (1958). Drawing

William Auerbach-Levy (American, born Belarus 1889-1964)[Michael Higgins as John Proctor, Margaret DePriest, and Ford Rainey as Deputy Governor Danforth in "The Crucible".] (1958). Drawing.

At the end of Act III, Williams and the other girls accuse Mary Warren, a servant to the Proctor family, of witchcraft in front of Reverend Hale and Judge Danforth. This accusation comes after Warren reveals to Proctor and the judge that the girls are lying about seeing the devil and practicing witchcraft. Acting transfixed and talking to an apparition of a yellow bird, seemingly showcasing Warrens ability to shapeshift and commune with the devil, the girls repeat Warren's renouncement of devil worship while they convulse onstage. Danforth leads Warren to confess, but for her not to be hanged, she accuses Proctor of conspiring with witchcraft. Placing the blame on Proctor enables her to evade death and keep her social standing within the group of young women. This scene increasingly drives the terror implicit in the play.

Film reel of Act III from the Old Vic production of The Crucible (2014) Courtesy of Digital Theatre

In actuality, the Salem Witch Trials were a terrifying form of mass hysteria whose likes had never been seen in the Americas. The ardor of accusations led to over 200 people being accused, and 20 of them losing their lives. Sociologist and Senior Fellow at the University of Virginia Isaac Ariail Reed has written on how the mass panic associated with the Salem Witch Trials works to affirm Roland Barthes's theories of resignification and metanarrative within the mythologies of the town. He states, "metanarratives provide actions to understand the 'underlying' significance of more specific stories, narratives of events and occurrences, and so on. Insofar, they can render such understandings, metanarratives are thus tools of rhetorical power." (Reed, 72) Reed discusses the metanarrative of the Salem Witch Trials in the form of the sermons given by parochial powers in the town. These sermons talk about the 'evidence' and accusations of witchcraft through the veil of the fear of the colonists' continual charter. Retrospectively, the Salem Witch Trials were not fueled with salacious details of personal affairs between children and grown men, as seen in Miller's account, but with fears connected to imperialism, nationality, and religion.

Tompkins Harrison Matteson (American, 1813-1884), Examination of a Witch (1853) Oil on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA

The historical backbone of how the Northeastern subset of the continental United States started is rooted in the Protestant Reformation (est. 1517) of the century prior. The Puritans, who inhabited New England during the colonial period, were a subsect of fundamentalist English protestants. The Protestant Reformation started with German theologian Martin Luther (1483-1546) distributing his Disputation on the Power of Indulgences, or 95 Theses, opposing the corruption within the clergy of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1534, the Protestant Reformation began in England when King Henry VIII (1491-1547) wanted to be granted annulment for his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536) to marry Anne Boylen (c. 1501-1536). When Pope Clement VII denied the request, mainly because the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, was Catherine's nephew, Henry assumed the head of the Church of England. By banning all ties to the Roman Catholic Church, Henry VIII established Protestantism as the main branch of religion in England, which would continue to create problems for centuries.

After King Henry died in 1547, there was a scramble for the throne, ending with the crown ending on Anne Boylen's daughter Elizabeth I (1533-1603). Before her reign, Elizabeth I's half-sister Mary I (1516-1558) brought Roman Catholicism back to England. After a brief period of religious persecution under Mary named the Marian Persecution, protestants were predictably upset, and Elizabeth restored Protestantism to England. Protestants were not impressed by Elizabeth's efforts and thought that Elizabeth could do more; in doing so, they formed the Separatist Church of England, which would go on to take the maiden voyage on the Mayflower (1620). These are the socio-religious underpinnings that lay the groundwork for the preceding events of New England.

A woodcut from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs depicts the burnings of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley. (1563) Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC.

Around a decade after the original pilgrims landed in Plymouth, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded. The English settlement, which controlled the areas around Boston and Salem, was governed by the Royal Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company, which was granted by Charles I (1600-1649). As a result of the English Civil War (1642-1651), Charles I was highly loathed by the people, who in response would abolish the monarchy, decapitate Charles I, and establish the Commonwealth of England. In 1660, Charles II (1630-1685) took the throne during the Stuart Restoration. He was invited back after Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), the republic's protectorate, died. However, Charles II is also highly unfavored, but this time in the colonies for his interest in centralizing power and having strong governmental control over the Americas in the 1660s and 1670s. Thus following a string of navigation, trade, and custom acts that increase taxes on the country's imports and exports. These acts continually lost England money, resulting in a Stop of the Exchequer in 1672.

Before the Stop of the Exchequer, Royal Commissioners were sent to New England to understand the violation and enforce the tariffs. While meeting in Boston, the council refuses Edward Randolph's (1632-1703) proposition. Afterward, his correspondence with the Lords of Trade back in England persuaded Charles II to revoke the charter in 1684. In a less economic sense, colonists were upset when the Massachusetts Bay Colony was ransacked during the King Philip's War (1675-76) and the colonists' fear of an absolute monarchy after the Exclusion Crisis (1679-81). The revocated charter was then replaced with The Dominion of New England, under the control of Edmund Andros (1637-1714), who would be jailed in Boston in 1689 after the Glorious Revolution (1688) when William III of Orange (1650-1702) and Mary II (1662-1694) were coronated and dissolved the highly unfavorable Dominion of New England. A new charter for the Massachusetts Bay Colony was granted in 1691 but did not reach New England until 1692.

The economic reasoning for this push and pull between English control over the colonies only tells half the story. The instability within the charters and quick succession of monarchs caused the fear associated with the metanarrative of the witch trials, but not the symptom. To understand why 'witches' were being persecuted, we need to go back to the Protestant religion. As stated prior, Protestantism was founded in opposition to the Roman Catholic faith. The two significant tenets of Protestantism are the lack of idolatry and the lack of selling indulgences. Protestantism wants to rid the Church of the splendors associated with the Medieval world. Resulting in what German theorist Max Weber (1864-1920) calls the "disenchantment of the world" in his text, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904).

George Henry Boughton, RA (American, born England 1833-1905) The Early Puritans of New England Going to Church (1867). Oil on Canvas. The New York Historical Society.

Professor of History and Religious Studies Carlos Eire believes that the Protestant Reformation aided the transition toward modernity by turning the world secular. Eire states,

as the clerics were desacralized, so were time and space. Gone were shrines, pilgrimages, and processions. Gone were the images and relics that connected the faithful to heaven. Churches were still special spaces, yes, but there was nothing inherently sacred about them. (Eire, 146)

By disavowing all forms of the preternatural and superstitious as forms of demonic intervention, the Protestants were able to rid the world of miracles, religious imagery, relics, belief in communion with the dead, and other forms of 'supernatural phenomena.' This opposed the Catholics, who had strong ties to monastic tradition, divine intervention, and sacralized space as tenets of their connection to the higher power.

The power struggle between Protestants and Catholics during the seventeenth goes further, explaining the rationale for the English tight grip on New England. In 1661, Cardinal Marzin, chief minister to King Louis XIII (1601-1643) and Louis XIV (1638-1715), died, leaving Louis XIV in chief control of the country. As a result, he starts constructing his magnum opus, The Palace of Versailles, a renovated version of his father's hunting lodge. Wishing to centralize governmental affairs, he and many French nobles moved into the palace in 1682. In the two decades, French designers Louis Le Vau (1612-1670), Andre Le Notre (1613-1700), Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), Francois D'Orbay (1634-1697), and Jules Hardouin-Mansart (1646-1708) transformed the humble lodge into a symbol of French opulence that glorified the French court establishing a dominant player in European politics.

The Catholic regime heavily influenced the French court. Professor of History Owen Stanwood notes that conflicts in England and America were "reactions to the perceived resurgence of global Catholicism under the banner of the French king, Louis XIV. When the Sun King began his program to reform the French state and expand his influence in the 1670s, he inspired various responses from his neighbors." (Stanwood, 482) Namely fear of French domination in colonial expeditions. It was widely believed that the French would indoctrinate the Indigenous population to Catholicism and rid the English of their colonial conquest. The Stuart officials wanted to grab ahold of the colonies to rival the opulence and power of the French regime. Making the navigation acts and high tariffs on the imports and exports were just the way to continually grow the empire under the guise of religious fear.

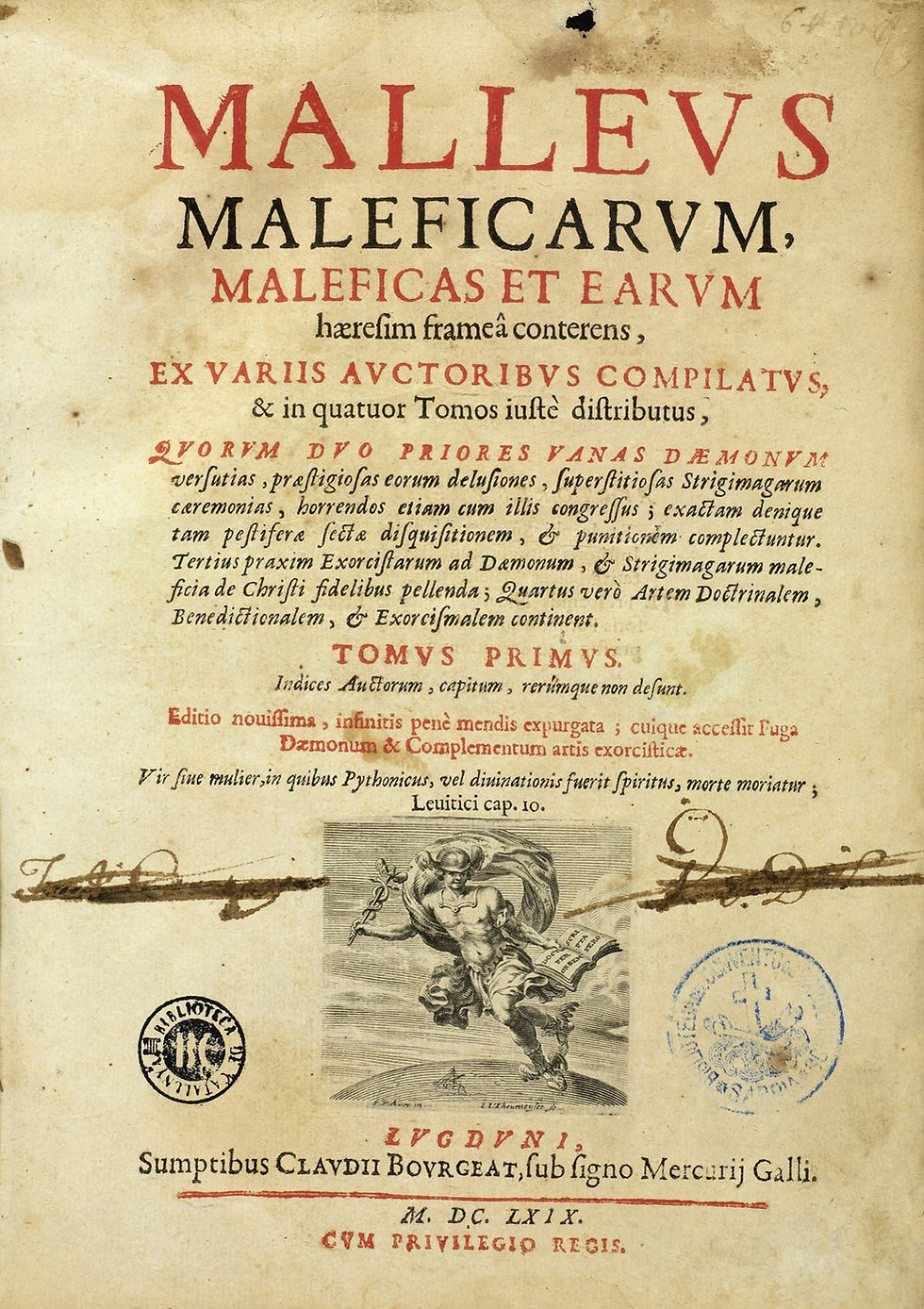

The history of imperialism, religious crisis, and economic strife in the New World landed us in 1692. The Salem Witch Trials were just one in a larger culture of witch hunts that evolved from the Medieval period. Witch hunts continually plagued Europe after the Christian world created fear tactics that shunned pagan superstitions, traditional medicine, and other forms of 'barbaric' religions. Among the essential steps in the standardization of persecution of 'witches' cemented itself with the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum (1486), which is a guidebook to demonize, accuse, and ultimately annihilate witchcraft practices. As the protestants wanted to rid the world of supernatural phenomena and all forms of divine intervention were seen as demonic, the accusations of witchcraft carried a severity that created mass panic.

Title Page of an edition of the Malleus Maleficarum dated 1669. BEIC

Reed suggests that the main reason for the witch accusations stems from the panic surrounding the lack of charter and the uncertainty developing on both sides of the Atlantic. Of the around 200 people accused, many were women, and it is stated that accusations were aimed toward 'women who inherited property and challenged the (essentially patriarchal working of the Puritan inheritance system." (Reed, 75) Reed uses the word property, which typically refers to places of habitation. However, during the Colonial and Revolutionary eras, this form of property was associated with a patrilineal line, from father to son. Professor of History Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has posited the importance of a 'movable.' These objects, such as furniture, textiles, baskets, and chests, "formed the core of a female inheritance." (Ulrich, 111) These objects, which moved from parent to daughter, were likely found in women's trousseaus and dowries, had both sentimental and monetary value, and helped to start a home. However, if women were seen as inheriting more than seemingly plausible, then envy would soon arise.

Unknown Designer (American) Cupboard (1670-1700)White oak, red oak, chestnut, hickory, red cedar,cedar. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Unknown Designer (New England) Needlework Picture of Pastoral Scene (c. 1750) Wool and silk ivory embroidery threads on a linen ground. Colonial Williamsburg collection

Unknown Maker (Boston) Oval Table with Falling Leaves (1690-1720). Black walnut and white pine. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Historian Kathleen Brown diagnoses, "As demographic pressures and economic difficulties increased the size of the poor and vagrant populations, English property owners actively pursued beliefs that the subordination of women, especially the impoverished, would contain the chaos and restore social harmony." (14) The accusations fill the metanarrative within the socio-economic structure that ministers like Cotton Mather (1663-1728) and Samuel Parrish (1653-1720) believed the colony should operate by. The crisis associated with the patriarchal codes of the late seventeenth century informs the reasoning for the accusations. Whether the accusations come from women being placed in competition with each other via the subjugation of patriarchy or from men wanting to rid women of any form of freedom or status they acquired, all forms of persecution go back to a crisis of masculinity on the macro and micro levels.

The reasoning for the accusations will be left to the archives and history books for now. I want to bring to the forefront the architecture associated with the period using the Salem Witch Trials as a hinge of historical importance. The mission of this research inquiry is to provide the historical foundations that built the Johnathan Corwin House and the Ropes Mansion, which occupy the same street but have vastly different styles of architecture. I believe we can employ Barthes's theory of signification and resignification to understand that architecture and design are not always about emulating the rich but can be used as a coping mechanism to deal with communal shame.

Unknown Photographer. Exterior view of the Old Witch / Corwin House, North and Essex Sts., Salem (c. 1940-1950). Photograph. Historic New England Collection

The Johnathan Corwin House stands at the corner of Essex Street and North Street. Towering over the street with a blackened facade and menacing nickname 'the witch house,' the house stands as a pillar of the Salem Witch Trials. It is one of the last standing structures with direct links to the trials, as it was used as a holding tank during pretrial examinations to speak with the accused. As previously discussed, Act III of The Crucible takes place in a room similar to how Corwin used his house before sending people to trial. The space was meant to get confessions of witchcraft; there was little mercy in the trials, and therefore, guilty until proven innocent was the primary modus operandi.

Within its design elements, the house is a saltbox from the First Period of construction. Although it is generally accepted that the house was completed by Johnathon Corwin in 1675 when he bought the property from Captain Nathanial Davenport, it was started long before possibly going as far back as the 1640s. A saltbox is a typical colonial form comprising two stories in the front, one in the back, a gabled roof, and a centralized chimney. This rudimentary form was vernacular to builders of the first period with little architectural training. They often resemble the post-medieval design of buildings with thatched roofs and timber construction popular in England before colonial expansion.

In present-day Salem, three structures away from the Johnathan Corwin House, a bright white Georgian home contrasts the previously-mentioned darkened facade. Today, The Ropes Mansion is typically associated with the 1993 Disney film Hocus Pocus, but it does have its history. This structure was built in the 1720s for Samuel Barnard, who moved to Salem after the death of his wife. It is a Georgian form with a gambrel slate roof and features two and a half stories. The design is heavily influenced by Palladian revivalism and profits symmetry and order of form. In this, the Ropes Mansion has a central door flanked by repeating windows and paired chimneys.

Unknown Photographer. The Ropes Mansion ( May 16, 1958 issue of Life Magazine)

Apart from the color of the two buildings, which stand on opposite sides of the spectrum, there are differences, and there is a reason apart from changing styles. Barthes's theories of signification and resignification can be placed into the permanent structures and design aesthetics that constitute and control our lives. In semiotics, the image of a house should only assume that the sign (the house) signifies the signified (people inhabit). However, the histories of these two places and the styles of their facades help add to the town's mythology through the easily digestible metanarratives for the public. In the case of the Salem Witch Trials, the Johnathan Corwin House goes through the resignification process and gains its nickname, the 'Witch House.'' Without understanding the historical significance, the name already associates the viewer with a particular experience. Preserving the history of the witch trials, specifically the Witch House is of more contemporary interest through the reinvigoration of Wiccan and neo-paganism practices in the mid to late twentieth century.

For the two centuries between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, witchcraft was less feared but still a social taboo. The Ropes Mansion, built in a new style three decades after the trials, covers up the fear and shame associated with the event. Reed affirms, "Salem quickly became a source of shame for those involved, and witchcraft was never again prosecuted with such violence and fervor in the North American English Colonies." (Reed 75) The shame associated with the 'violence' and 'fervor' has the power to transform the landscape of New England. The semiotic codes of design are constitutive of the architect's and builders' social world. The two buildings, separated only by a church, tell a story of power, imperialism, religious intolerance, and fear of self-determination.

B. Anthony Stewart (American, 1904-1977) Witch Jail in Salem Recalls Witchcraft Horrors of 1692 from the September 1945 issue of National Geographic. Internet Archive

The tempering of fear associated with the charter, British imperialism, French luxury, and women's inheritance sets the stage for the coming years of revolutionary thought. When the inhabitants of the colonies learned that they were simply pawns in a game of European empire creation and knew they needed to fend for themselves, the thoughts of the Enlightenment came into fashion in the eastern seaboard. By covering up the past with new architecture, New England was able to help construct the mythologies associated with the area. The depoliticization of speech evokes the romanticism found under covered bridges enveloped in the fiery color palette of autumnal splendor.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Translated by Jonathan Cape Ltd. New York: The Noonday

Press, 1972. Print

Breslaw, Elaine G. “Tituba’s Confession: The Multicultural Dimensions of the 1692 Salem

Witch-Hunt.” Ethnohistory 44, no. 3 (1997): 535–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/483035.

Brown, Kathleen M. Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race

and Power in Colonial Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 1996. Print

Burns, Margo, and Bernard Rosenthal. “Examination of the Records of the Salem Witch

Trials.” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 3 (2008): 401–22.

Cummings, Abbott Lowell. “The Domestic Architecture of Boston, 1660-1725.” Archives of

American Art Journal 9, no. 4 (1971): 1–16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1556857.

Eire, Carlos. “Incombustible Weber: How the Protestant Reformation Really Disenchanted

the World.” In Faithful Narratives: Historians, Religion, and the Challenge of

Objectivity, edited by Andrea Sterk and Nina Caputo, 132–48. Cornell University

Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt5hh14x.12.

Greig, Hannah, and Giorgio Riello. “Eighteenth-Century Interiors-Redesigning the

Georgian: Introduction.” Journal of Design History 20, no. 4 (2007): 273–89.

Miller, Arthur. The Crucible: A Play in Four Acts. London: Penguin Books, 2015.

Reed, Isaac Ariail. “Deep Culture in Action: Resignification, Synecdoche, and

Metanarrative in the Moral Panic of the Salem Witch Trials.” Theory and Society 44,

no. 1 (2015): 65–94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43694747.

Stanwood, Owen. “The Protestant Moment: Antipopery, the Revolution of 1688–1689, and

the Making of an Anglo‐American Empire.” Journal of British Studies 46, no. 3 (2007):

481–508. https://doi.org/10.1086/515441.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an

American Myth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf .2001. Print.

Comments