My Girl Back Home: Women Left Behind in World War II

- TJ Moss

- Oct 15, 2023

- 15 min read

We’ve all heard of the infamous ‘dear john’ letter. Immortalized in popular culture, these mournful letters express their deepest sympathy when a woman leaves her partner who is off at war. Whether for practical reasons such as economic disparity or insufficiently met carnal needs-- these women have found another avenue in which to fulfill their desires. Written to thousands of men during wartime, their rise in popularity was brought during the Second World War (1939-1945) when men fought both in Europe and in the South Pacific. Up until this point, the women back home with their victory gardens and newfound career endeavors had never been granted such prolific amounts of liberty in the United States. Whether they worked in factories producing ammunition for soldiers, as nurses tending to the infirmed, or in clerical jobs, these women were a vital part of the continuation of the American population during wartime. Capitalistic expenditure and dependence on women during the World Wars has been studied and researched heavily over the past fifty years by scholars such as Maureen Honey (1945-), D’Ann Campbell (1949-), and Marlene Kadar (1950-). What can largely be understood from academics of women during this time is the flourishing of women’s self-determination within the economic sphere. What can largely go unforetold is womens need to do both the manual labor of a job with the emotional labor of homelife with little help from others.. This balancing act that without mutual support from female friendships, families, and, or partners could lead to the deterioration of a love is where i want to investigate further. The passage of time and our own family folklores of parents’ and grandparents’ love stories that worked have shielded this large section of love lost and the despair found on the other side of freedom. Why were these women villainized and how have they been depicted in the media’s social current.

On a purely anecdotal note, I am the result of wartime love that fizzled. My grandfather was stationed in Hawaii during World War II. He had a seemingly lovely first wife and a child, but after years alone she found her needs unmet. As the story ends without the salacious family gossip, my grandfather returned home to be greeted by his wife, his child, and another baby that could not have been his. He left this woman, and she continued a relationship with the other man. A few years later, my grandfather met my grandmother and they fell in love. The rest is a history tinged with serendipity and a bad day turned into the start of his rest of his life. Upon meeting my grandmother, he knew he would marry her and start a new life with a new child, completely separated from his former wife and child. As far as my knowledge goes, there was no contact between him and the life he left behind. It is just the prologue to my own family tree. I have often wondered about his first wife and the son he had- who were they, what did they do, where were they now. All answers of which are, by now, taken to the grave and withered away.

Norman Rockwell (American 1894-1978) Rosie the Riveter (1943) Oil on Canvas. Private Collection.

J. Howard Miller. (American, 1918-2004) “We Can Do It!” (1943) Poster. National Museum of American History at The Smithsonian, Washington D.C.

The most enduring images of women during the second world war operate in two different categories. The first definition of womanhood is wrapped up in Norman Rockwell’s (1894-1978) Saturday Evening Post Cover Rosie the Riveter (1943) and J. Howard Miller’s We Can Do It! (1943) poster for Westinghouse Electric. The Miller image, in particular, has gained a semblance of ubiquity when thinking about the Second World War’s visual culture. Professor James Kimble has challenged many of the misconceptions of the false Rosie. The “We Can Do It!” poster is one of 42 prints in a series created by Miller for Westinghouse and has less feminist overtones when looking at the set. Nonetheless, these images which both showcase working women have defined for subsequent generations what wartime womanhood might have looked like: Strong, patriotic, and resourceful. Leila J. Rupp has studied the material culture of the time and has concluded

“The blueprint [as shown from a 1942 Ladies Home Journal survey] showed how little Rosie’s wartime image challenged traditional expectations. The ideal woman of American fighting men was short, healthy, and vital, devoted to her home and children, able to participate in at least one outdoor sport, and font of a moderate amount of dancing.” (151)

No matter the ubiquity of the Rosie’s today, there was a far more dominant form in American visual culture that had been bubbling up since the late nineteenth century.

Al Parker (American, 1906-1985) Cover for Ladies Home Journal (Dec. 1939). Lithograph.

Al Parker (American, 1906-1985) Cover for Ladies Home Journal (March 1943). Lithograph.

Al Parker (American, 1906-1985) Cover for Ladies Home Journal (July 1945). Lithograph.

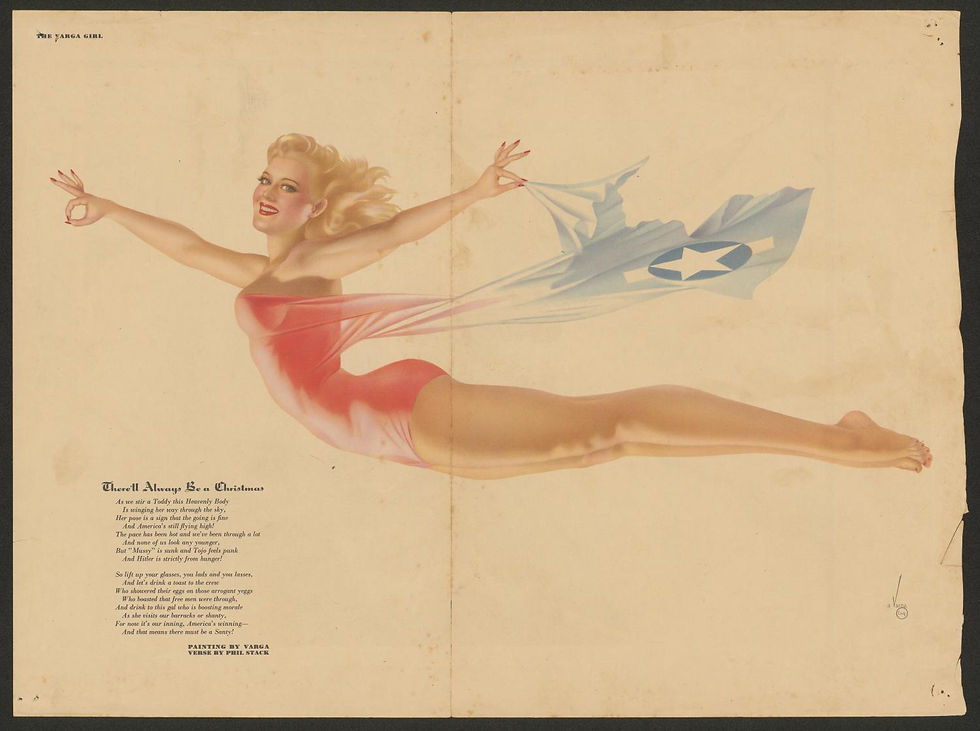

This other pervasive view of womanhood that reached its fever pitch in the 1940s was the pin-up girl. Whether illustrated by Gil Elvgren (1914-1980) , Alberto Vargas (1896-1982), Enoch Bolles (1883-1976), or George Petty (1894-1975), these seductive tempresses upheld traditional conceptions of white femininity and beauty standards to ease masculine anxieties. These anxieties gained traction due to the importance of industrialization and urbanization that flourished in the United States after the Civil War (1861-1865). These sexualized images of women were not only illustrated by playing out on the silver screen. Women like Rita Hayworth (1918-1987), Betty Grable (1916-1973), and Anna May Wong (1905-1961) became pillars of sexuality in the golden age of hollywood. Maria-Elena Buszek has stated

“The juxtaposition of fantasy and reality in [pin-ups] reflected American propaganda campaigns that encouraged women to emulate and mean to idolize female types normally vilified during peacetime and actively discouraged during the depression— powerful, productive women in professions and the military, who’s beauty and bravery resulted in large part from their very entrance into those spheres.” (185)

Their bold and bawdy nature shows the dichotomy around feminist concerns of both owning their sexuality and only being seen as a sexual object for masculine appetite. With these two opposing images, soldiers and housewives were placed at odds with what femininity would look like during the war years.

Alberto Vargas (Peruvian-American, 1896-1982) There’ll Always Be a Christmas (Dec. 1943) Print. Esquire Magazine

Where does that leave women who were not boisterous and strong-willed factory workers or glamorous pin-ups. Where does that leave regular housewives, mothers, teen girls? Does the lack of representation show these women that they were not patriotic enough or challenging norms of femininity? Norman Rockwell’s lesser known painting Coming Home (1945) paints a portrait of a soldier's warm welcome after returning from war. He is met by friends, family, neighborhood kids, and to the left of the portrait, a blonde-haired young woman hides sheepishly against the brick building. Knowing it is not the proper moment in which her lover and her will have their reunion she allows his family to greet him first. The vagueness written into the subtext of the painting leaves their relationship at an unidentified plane. With her girlish red ribbons adorning her hair, the viewer can denote that she is not the wife. The girl and the soldier look like teenagers.

Norman Rockwell (American 1894-1978) Coming Home (1945) Oil on Canvas. Norman Rockwell Museum.

The soldier does not return the strong, valiant man one may think of when imagining a veteran. His scrawny appearance and lack of musculature points to his adolescence. This image while on the grander scale notes how young the men of World War II were while fighting. Due to the way in which the war was glorified for Hollywood, one might think of Robert Taylor (1911-1969), Frederic March (1897-1975), or Lawerence Olivier (1907-1989) to be the man returning home. However, many of the men were just average teenagers fighting overseas. American art historian and professor at Stanford, Alexander Nemerov brings up an interesting point when reading this painting from the soldiers point of view. He states,

“If one follows their paths of vision— that of the mother, for example— the eyes oddly converse on various points behind him, almost as if some other fighter or some other scenes not visible in the canvas, attracted their attention. Their soldier is like an absent bystander to their excitement even as he is the cause of it.” (65)

As if the soldier is not truly returning home due to death, but what the hero’s welcome might have looked like to the ghost of a boy far too young to fight. This sober reading of the portrait does not fully fit in line with the Norman Rockwell oeuvre. However, it is without a doubt that no matter if the boy is returning or not, everyone is changed at the onset of war.

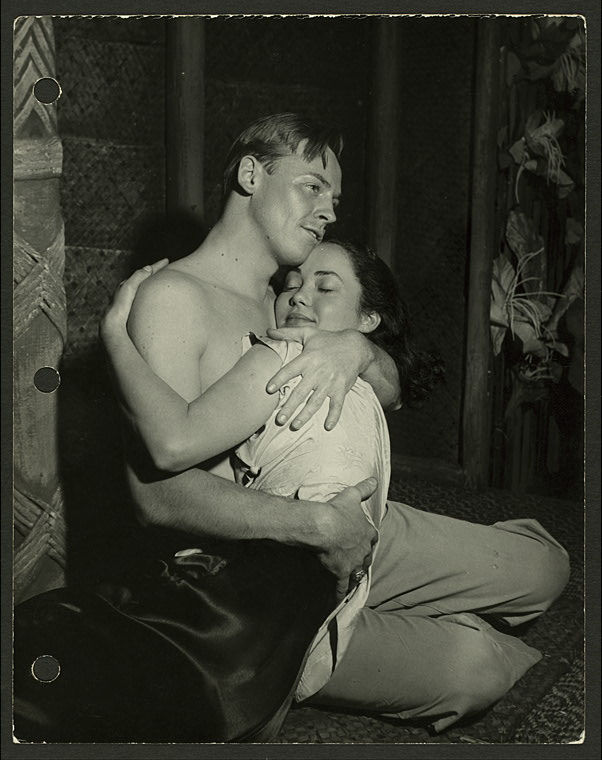

John Swope (American, 1908-1979) William Tabbert (Lt. Joseph Cable) and Betta St. John (Liat) in South Pacific (1949) Photograph. NYPL Digital Archives

This painting reminds me most of the love triangle between Lieutenant Joseph Cable, his "Girl Back Home”, and Liat, a woman from the fictional island of Bali Ha’i from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific (1949). Based on a collection of short stories by James A. Michener (1907-1997) entitled Tales from the South Pacific (1947), the musical weaves a story of two entwining love stories throughout American occupation in the South Pacific. The main love story concerns Nellie Forbush, a young and naive nurse who falls in love with worldly-wise and European older gentleman Emile De Becque. The other romantic storyline which comes from the original Michener text, “Fo’ Dolla’” concerns Joe Cable, a young American lieutenant who falls in love with a young Tonkinese woman from the island named Liat. Liat is a caricature of a young Asian woman that American soldiers fell for during wartime. In the same vein as Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904) or Anna May Wong’s character, Lotus Flower, in A Toll and The Sea (1922). These doting, submissive tropes stereotype Asian women as subservient to the white man and still have ravages in contemporary art.

A. Frances Nuyen (French, 1939-) as Liat in Joshua Logan’s South Pacific (1958). Distributed by 20th Century Fox

However, in the South Pacific, there is a change in fate for the woman. In both Madama Butterfly and A Toll and the Sea, the female leads both choose death over living a life without their white lover. At the end of the musical, while Nellie is focused on the fate of her relationship with Emile, of which she ruined by her own racism, Bloody Mary, Liat’s mother, comes and asks Nellie where she can find Joe. In her words of sorrow, Bloody Mary explains that Liat will only marry Joe as she is the only man she will ever love. Subsequently, Nellie mournfully tells Bloody Mary that Joe has died. He did not escape the mission that he and Emile had been on. Although the Joe and Liat storyline hold second billing to the Nellie and Emile romance, it is the lynchpin of the story.

Joe Cable is a young Princeton graduate who hails from a wealthy Philadelphian family. He sings, along with Nellie, “My Girl Back Home” in which he explains how clearly cut out his life upon returning to Philadelphia will be. He is meant to go back home and marry a woman of his same social stature that has been picked out for him.

“My girl back home— I’d almost forgot! A blue-eyed kid— I liked her a lot.

We got engaged— Both families were glad; And I was told by my uncle and dad That if I were clever and able They’d make me a part of a partnership Cable, Cable—and Cable!”

In a different scene with Emile, Nellie divulges that she is also betrothed to a man back home:

“Gosh , I don't know, it was more like I was running to something. I wanted to see what the world was like, outside of little rock, I mean, and I wanted to meet different kinds of people. That day that this was taken I promised Charlie Benedict that when I came back I'd marry him. He’s a cashier at a bank, he has a mother to support. I don't think he believed me when I promised to marry him. Maybe I didn't believe myself.”

In this, there is a role reversal of the woman who leaves home and finds new love outside of her hometown. Unlike Joe who left his girlfriend behind as is depicted in the Norman Rockwell painting, Nellie is a United States Nurse and seeks adventure on her own terms. The musical plays a trick on the audience. They spend the entirety of Act I falling in love with the endearing character of Nellie, but the finale allows a look into a darker side of Nellie’s personality. She is confronted with the fact that Emile, not only has two children, but they are half Asian. She flees the scene of their date unable to deal with these feelings of racism. She never really wanted to “meet different kinds of people”, only different people that looked exactly like the ones in her hometown.

This musical returns frequently to the idea and fictionalization of a blonde haired, blue-eyed all-american beauty. She is distilled in both Nellie and Joe’s girl back home. Andrea Most suggests “Nellie establishes herself as the embodiment of American youth, optimism, energy, and power, the life force of the island…She demands that the audience identify with her, a familiar, recognizable all-American girl next door. Her assertive normalcy serves to throw Emile’s differences further into relief.” (321) However, this all-american quality has a darker underbelly shown in Nellie’s reaction to Emile’s past. Her feelings of insufficiency plague her relationship and lead to her racism against Emile’s first wife and children. The two romantic couples seem to be dramatic foils which aid in the message that Rodgers and Hammerstein were meaning to convey. They work the musical to elicit a human empathy toward racial equality after Americans' hatred of Asian peoples catapulted from the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The musical was meant to shift the needle forward in how Americans saw people of color by tugging on the heartstrings. This is why Liat cannot die and Joe has to. This reversal of the Madama Butterfly trope helps to foundationally support the vision of love and loss.

Philippe Halsman (American, Born Latvia 1906-1979) Barbara Luna (Ngana), Michael or Noel DeLeon (Jerome) and Mary Martin (Nellie Forbush) in South Pacific. (1950) Photograph. NYPL Digital Archives.

The catalyst of this musical is Joe’s song “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught”. This song arrives in Act II when Emile asks Joe why he and Nellie are filled with prejudices that hamper love. He explains that it is something that is built into American social relationships and passed down through generational hate. The Girl Back Home is although a viable candidate for the American dream, their relationship lacks the passion that Liat and Joe have during the course of the show. The main problem forms from the power imbalance and the lack of coherence within their love story. At the beginning of the show, Liat only speaks French as she lives in French Polynesia. It is through falling in love with Joe that Liat learns to speak English to communicate with him. This bit of magical realism that love transcends all languages always prioritizes the colonial language, usually English. This orientalizing factor that places not only the woman under the man but the colonized country under the imperialist helps even still to move forward the American Dream that is built on the racism that the musical is trying to circumvent.

Poster from the Royal National Theatre’s South Pacific (2002)

Poster from Lincoln Center’s South Pacific (2008)

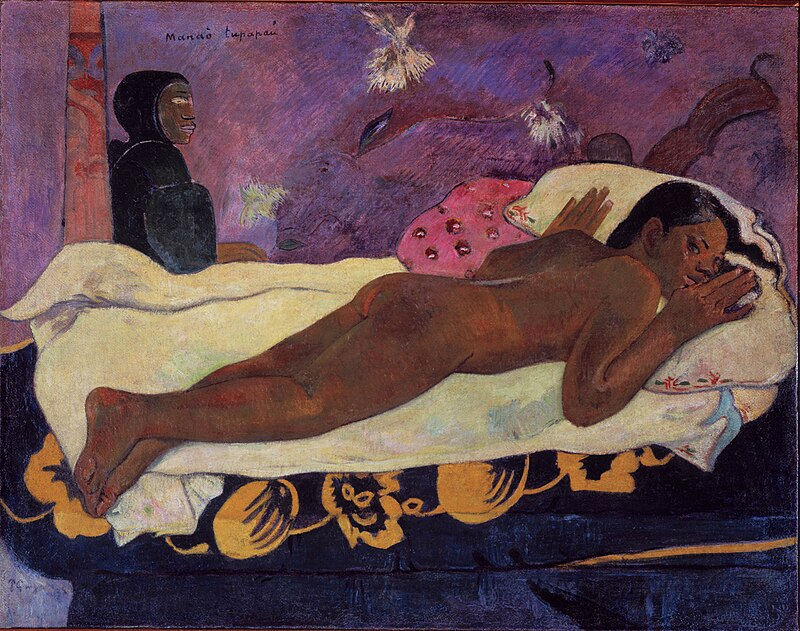

While looking at the two covers from the playbills and cast recording of South Pacific from the Royal National Theatre (2002) and the Lincoln Center production (2008), viewers can observe the two myths being presented. The 2002 cover presents the ideal of American Exceptionalism with the pin-up style painting on a military grade aircraft. The central image represents Nellie and Emile’s torrid love, however there is a misleading message in the image. With it being painted on the side of a plane, it seems as though the love is ripped apart by the war, instead of Nellie’s prejudices. However, in the 2008 cover, the central image of Nellie during the Honey Bun sequence surrounded by soldiers and the indigenous population looks at the fetishization of the land. There is a distinct reference in the style of painting to French painter Paul Gaugin (1848-1903) who is noted for his paintings of French Polynesia. It goes without saying that Gaugin was involved intimately with many underaged women of the islands even painting them in sexualized portraits such as The Spirits of the Dead Watching (Manao Tupapau) (1892) who was modeled after Gaugin’s ‘wife’ who was only thirteen years of age. Although Liat’s age in South Pacific is never specified it is known that she is still in her teenage years between sixteen and eighteen, where Cable must be older than twenty-one due to being a college graduate. These age differences between the white man and indigenous girl facilitate the orientalist and fetishistic view of young women of color further.

Eugene Henri Paul Gaugin (French, 1848-1903). The Spirits of the Dead Watching (Manao Tupapau) (1892) Oil on Burlap. Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

Although the audience does not know the age of Cable’s betrothed, it is more than certain that she is a suitable age for marriage in the American worldview. In fact, apart from a few lines in “My Girl Back Home” we hardly hear about the girl that is left behind. The song is more importantly a bonding moment between the two central Americans who must overcome their racist tendencies to find love. One film that does touch on the girls left behind is Waterloo Bridge (1940). Based on the play from 1930 and the subsequent film adaptation from 1930. The film version from 1940 takes artistic liberties with the source material in order to have a more melancholic and saccharine ending. The film opens in Britain at the onslaught of the Second World War, in a narration, you hear the male lead, Roy Cronin (Robert Taylor) reminisce about his former lover Myra Lester (Vivian Leigh) which all took place during the First World War (1914-1918). Myra at the start of the film, is a ballerina with a strict ballet madame. After disobeying the madame’s orders not to see Cronin, she is dismissed from the company, forcing her and her best friend, Kitty (Virginia Field) to find new jobs with little talent for anything other than dance.

Robert Taylor and Vivian Leigh in Mervyn Leroy’s Waterloo Bridge (1940) Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Before being thrown into poverty Myra and Roy get married, right before Roy leaves for combat. Unfortunately, with little money for food and rent Kitty, first, and then Myra, become sex workers who solicit men on Waterloo Bridge. Through the first half of the war, Myra stays loyal to her husband, even offering to have lunch with his mother. However, due to a misprint of his death, Myra spirals uncontrollably and is never able to recover, finally falling into the sex trade in order to numb herself from the devastating news. In a brief moment of fate, Roy returns to Myra, as in love with her as he was the day he left and is now prepared to give her the life she craved prior to war. The couple goes to Roy’s estate and stays with his family. Unable to deal with the shame of her sexual proclivities while Roy was away she flees and eventually takes her own life on Waterloo Bridge.

This melodramatic film brings up the shame and disparity that war can have on the people left behind. The biggest myth of the Second World War is of the happy housewives given a job easily and readily reverted to traditional gender roles when her husbands came home. James Kimble has noted

“Women on the factory assembly line faced prejudice, sometimes from men, sometimes from other women of different races. They were almost always paid less than men for equal work and, near the end of the war, they experienced tremendous pressure to return their jobs to war veterans. Most of these women were not married housewives, Instead, they were single women who were already working at lower-paying jobs and who entered the factories primarily to increase their salaries.” (534)

These women had faced hardships and economic problems due to rationing and lower supply chains, and these jobs were not easily accessible. This brings us back to the Miller poster’s myth of inclusion. The “We Can Do It!” image was not and was never meant to be a recruiting poster for female liberation, it profited only the workers of Westinghouse Electric, many of them still men. With the average age of 26, not all men were enlisted to fight so although many see wartime as a female utopian dream of excelling past misogynistic standards, this was never the reality. Older men and men without the right health were left to continue their lives. Like in South Pacific, if racism is a generationally passed down trait that happens within families and popular culture, so is misogyny.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, 1828-1882) Found (1881-unfinished) Oil on Canvas. Delaware Art Museum

Emile Berchmans (Belgian, 1877-1947).Winter variétés, La Dame aux Camélias (1920). Print

Vivian Leign as Myra Lester in Waterloo Bridge (1940)

If Liat personifies the "Lotus Flower" archetype of nineteenth century fiction, then Myra fulfills the role of the "fallen woman". Defined by her descent into sex work, the fallen woman has been a trope in art, literature, and theatre since the bible dammed mans fate on Eve in the Book of Genesis, but full gains traction in the nineteenth centuries obsession with decadence. One may think of Marguerite in Alexandre Dumas Fils’ La Dame aux Camélia (1848), Tess in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D'urbervilles (1891), or even Older Sister in D. W. Griffith’s The Painted Lady (1912). This hyperfixation of feminine chastity leads back to the masculinity crisis of the late nineteenth century that facilitated these sexualized images of women. It is not without early pin-up girls that men can both express their sexual appetite and repulsion for female sensuality. Dawn Schmitz points to the overt urbanization and industrialization for the masculinity crisis that men feel after the Civil War. The dream of being a cowboy out west conquering the land died when the American mainland was completely conquered and dreams of abundance took over. It is capitalism that breaks down the need for strict gender essentialist roles, so men sell the idea of sexualized women to the detriment of the lived female experience. Measuring up to feminine perfection and failing toward vilification has been the fate of women since the beginning of time, but the economic prosperity of World War Il only heightened the problem.

Patriarchy was not built to fail. Through careful domination tactics, the systems of oppression always understood an underclass of women to heighten male authority. What was unforeseen was the inevitability of a world war at the height of global superpowers and capitalism. Patriarchy created what would unquestionably unravel the oppressive forces. Unfortunately, 1945 was not met with an equal society but a wave of conservatism that threw women back into the domestic sphere. However, many women never left the domestic sphere until the ramifications of these housewives' children started to speak out in the 1960s and 1970s. There is a reason why we talk about feminism during the war years but not a feminist movement. Design historian Penny Sparke has illustrated “Until the separate spheres are consigned to the past and domesticity becomes a valued ideal of both men and for women, the exercising of taste will continue to play a key role within the gender politics of everyday life.” (172) Patriarchal concerns such as the infantilization of women, unequal pay, and unbalanced emotional labor will continue to fester underneath the surface of society. I will ask more plainly, were the women who left behind ever villains or just playing by male rules in a world that was set up to watch them fail?

Comments