The Mini Skirt: Redefining Sex, National Identity, and Feminism in 1960s London

- TJ Moss

- Aug 12, 2023

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 15, 2024

British Society for The Protection of the Miniskirt (1966)

In 1966, a group of British women protested in front of the House of Dior in London. Dawned in mini skirts and carrying picket signs, the group called themselves The British Society for the Protection of the Miniskirt and were protesting the conservatism of French legacy fashion brands. The protest created conversations about rebellion against fashion's subjugation of women. Throughout history, shocking fashion statements have made their way into the canon of emblematic design. However, no garment was as revolutionary or as polarizing as the mini skirt. Today the mini skirt is a global phenomenon that has been irreversibly tied to the fashion industry of London during the 1960s; a place and time for the flourishing youthquake. The designers associated with the design rejected predisposed modes and forms of fashion to radicalize young women's roles in society and solidify British national identity.

Constantin Alajalov (American, born Russian 1900-1987), Moonlit Future, Saturday Evening Post, (August 1959). Lithograph print (?).

After World War II, the prosperity of Western postwar life resulted in a society influenced by consumerist goods. Industrial and commercial design slowly gained popularity during the interwar period, namely in America and France. However, capitalist endeavors took over the Zeitgeist of western markets after the war ended. This is not to say that the world was without problems. Britain, along with most European countries, still had rations on goods such as food, petrol, and fabric until 1954, seven years after the United States derationed. In European countries specifically these austere wartime rations were used to maintain the empire by alleviating material goods from colonial exploits to decrease self-liberatory affairs. With the end of rationing and the austerity mindset came the British economic prosperity that the United States had been experiencing, characterized by what some call "'the Great Compression’.

Roger Mayne (British, 1929-2014) Girls, Teenage Night, Parkhill, Sheffield (1961)

The economic boom intermingled with social upheaval which challenged facets of British life during the period. British lifestyle and cultural capital would be reinvented due to the immense socio-political challenges of the late 1950s and early 1960s. This resulted in a reformation of British popular culture that allowed Britons to solidify a national identity based on consumerism spending. The 'youthquake' as coined by Diana Vreeland, former Editor-in-Chief of Vogue, was a time when designers, advertisers, and cultural critics started to market toward young adults and teenagers. Teenagers of the period were more likely to find employment for extra spending cash but because they did not experience poverty in the way their parents and grandparents had, they defied self-restraint in their consumption. Subsequently, new demographics were born: the teenager, the junior, the young adult.

Advertisements from Sears Catalog (Spring/ Summer 1964)

The prime market of the day was the young, single female in the late-teenage to early adulthood bracket. Women had been gaining prominence in British society since the early twentieth century, but the return of conservatism and recontextualization of domesticity in the 1950s had backlash in the feminist discourse. Although the consumerist economy of the postwar period was predicated on ‘traditional’ family structures, this is where women started to redefine gender conventions. The young women and girls in the 1960s would have grown up either alongside these detrimental images of women or raised by women who were subverted by them. By challenging the notions of domesticity, the women of the 1950s and 1960s started to examine the scarcity of visibility and equality as formations of the patriarchy.

One of the largest issues that concerned the blossoming Women's Liberation Movement, which would not be named until the latter half of the 1960s, was sexual liberation. Unlike previous generations, women of the 1960s were able to enter the workforce and abstain from marriage and childbirth as feminists who believed that liberty and license were the answer to ending patriarchal oppression. Through the personal and political, feminists fought for legal and social autonomy. The sixties saw the birth of not only teenagers and new clothes for them, but the contraceptive pill in 1963 , reformed laws concerning matrimonial autonomy, and the limited right to abortion in 1967. The politicization of the sexual liberation movement created new technology and material culture that combated traditional modes of femininity.

However, the mythology surrounding the contraceptive pill exaggerates the loosening of sexual constraints in British society. Sexual liberation is represented as the emancipation of women from the restrictions of a culture that was obsessed with chastity. What is forgotten is the reality of the pill, which instructed that most contraceptive users needed to be married women. It was not common for young women and teenagers to be prescribed the pill as it was not utilized as a hormone stabilizer during menstruation as it is today. However many feminist were weary of contraceptives as men were often known for their exploitation of women through casual sexual encounters. The subordination of women through the guise of their own liberation challenged feminists to accept or deny contraceptives as empowerment. The pill also meant that women were less likely to use the economic burden of childbirth to deny mens unwanted sexual advances.

Regardless of the realities of womanhood during the sexual liberation movement, the trope of the sexually independent young female still persisted. Represented by Cosmopolitan Editor-in-Chief and author of Sex and the Single Girl (1962), American Helen Gurley Brown, allowed for nuanced conversations about sexuality, feminism, and patriarchy. Gurley Brown is often seen as the antithesis of other famed feminists, such as Betty Friedan, who wrote The Feminine Mystique the year following Sex and the Single Girl. Opposed in their views of female empowerment, these women are icons of feminist pedagogy. It is the choice for women to decide between liberating themselves through sexual encounters or through work that sets up the disjointed points of view in the feminist movement. Of course, these are not the only two options for women, now or during the 1960s; however, they are large sectors of philosophy that create tension. Despite the feminist dialogs created by both authors, their differences stem more from their intended audience. Gurley Brown wrote for young, single career women.Away from the confines of marriage, Gurley Brown challenged the 'suburban' marriage norms and created a space for a new kind of woman; a sexually active woman aware of her age, gender, and body, defying the codes of traditional femininity.

Due to the overlapping forms of feminist thought, self-fashioning became an important issue for young women of the day whose hopes and anxieties manifested themselves into popular culture and clothing design.. The most enduring design resulting from the feminist debates was the mini skirt. However, although contested, the origins of the modern mini skirt started in 1960s London as a reaction to the youthquake and feminist ideology. The mini skirt is defined as any skirt with a hemline reaching anywhere from the middle of the thigh to just above the knee, getting shorter throughout the decade. Seemingly the mini skirt was fashion designers response to active young women like Gurley Brown who were seeking a new form of expression as the New Look no longer suited them.

Mary Quant at her apartment in Draycott Place, London, c. 1967

The contention surrounding the mini skirt's forms from the inability to trace designer lineage. Three credible designers have been credited with the design, namely Yves Saint Laurent, Andre Courréges, and Mary Quant. Graduate of Goldsmiths College of Design in London, Quant has been described as the inventor of the mini skirt. However, through interviews and autobiographical material, she states that she did not invent the garment, she just put what she saw young women wearing on the streets of London into mass production. Women had been shortening and altering their hemlines long before Quant, and her husband, Alexander Plunkett-Green, opened their boutique, Bazaar on Kings Road, in 1955. In 1963, Quant added mini skirts, named after her favorite automobile, The Mini Cooper, to her boutique under the more affordable Ginger Group label. The mythology of Quant's design is disseminated through her naming the skirt.

(Left) Yves Saint Laurent (French, 1936-2008) Mini Dress (1967). FIDM

Boutiques, like Bazaar, stand away from the high culture of haute couture that initially defined the fashion industry. Despite fashion houses' propensity for traditional designs aimed at affluent older women, the mini skirt has origins in high fashion. In 1957, Christian Dior, famed French couturier, who revolutionized post-war fashions with his 'New Look' (1947), died. The fashion house, which exemplified femininity and historicizing silhouettes, required a new creative director. Prior to passing, Dior was enamored with the young designer Yves Saint Laurent upon the introduction from Michel de Brunhoff, editor-in-chief of French Vogue. Saint Laurent was hired as Dior's assistant and, after Diors' passing, was in charge of the fashion house. In the Spring/Summer collection of 1958, Saint Laurent introduced the trapeze style dress. Far from the wasp-waist dresses with yards of fabric that Dior pioneered, this simple a-line style had a shorter hemline and looser fit. Along with Saint Laurent's draft into the Algerian war, YSL’s progressive approach to fashion aided in the departure from the house of Dior.. Saint Laurent would leave to create his eponymous fashion label in 1962 and continue to design fashions that spoke to the counterculture of the 1960s, including space-age and mod garments.

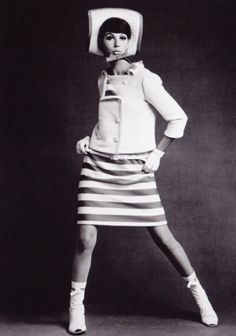

(Below) John French (British, 1907-1966) Simone d'Aillemont in dress and jacket by André Courrèges, (1965)

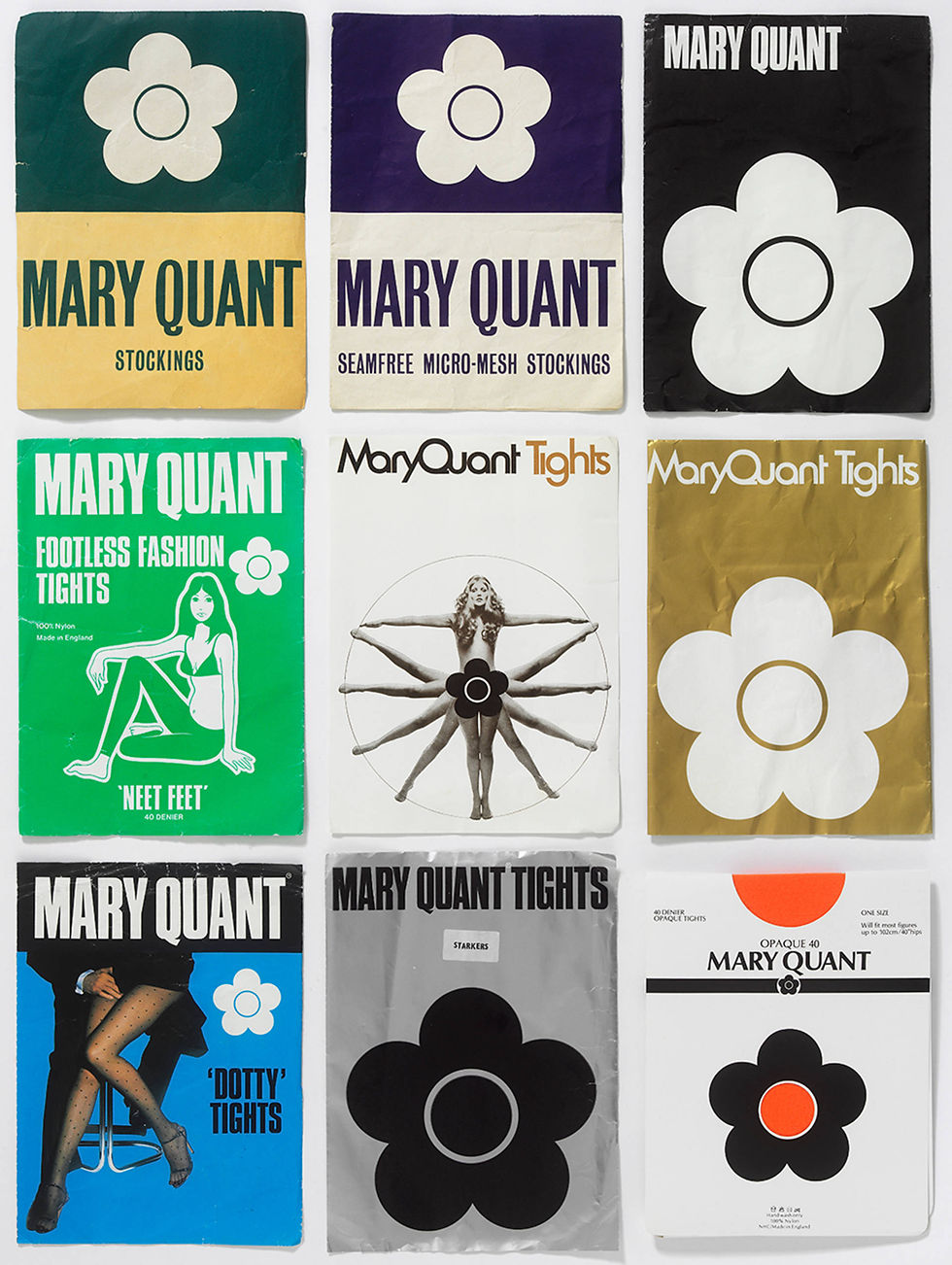

A year prior to Saint Laurent starting his label, Andre Courréges, who worked under Cristobal Balenciaga, opened his own fashion house. Courréges is more known for introducing the white go-go boot (1964). However, the same year as the Courréges Boot debuted, he showed mini skirts on the runways. This acceptance of shorter hemlines in couture spoke to the importance of youth culture in design. According to author Dorothy D. Prisco, "for the first time, fashion trends were being made by youth in the streets rather than being dedicated by the fashion designer elite" who would later design garments around youth culture (“From Neckties to Blue Jeans: Student Dress and Social Change.” 54) In this period, the youth and the mini skirt would go through even more liberating changes. In 1963, fashion journalist turned museum curator Ernestine Carter deemed it "the year of the leg." By 1965, mini skirts had risen from just above the knee to death-defyingly short due to male intervention. This modification to the garment demanded the need for patterned tights, stockings, and matching socks.

Selection of Mary Quant stockings and tights in original packaging, 1965 – 83. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As the mini skirt became even more a symbol of young womanhood, they changed systems of oppression. Along with its acknowledged associations with the sexual liberation movement, it also changed school dress codes and modes of self-fashioning in school environments. Although Quant has stated that her inspiration was school girls, shortened hemlines were not as short until they became mainstream By challenging school dress codes, this garment allowed for the breakdown of formerly held beliefs of school hierarchy and conservatism in the system.

Jane Birkin (1946-2023) as Penelope in Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969)

Bert Stern (American, 1929-2013) Jean Shrimpton (British, 1942-) for Vogue (1965)

Bert Stern (American, 1929-2013) Twiggy (British, 1949-) for Vogue (1960s)

The importance of the mini skirt, and other youthquake fashion, changed contemporary beauty standards. A new aspirational childlike physique was a reaction against the 1950s hourglass shaped models and actresses; the look took away the importance of a womanly body and allowed women of a different shape to prominence. However, the thin adolescent body type is not without controversy. Women who did not fit into the age or weight intended for the mini skirt still wanted to remain fashionable and felt excluded from the new silhouette. Models like Jane Birkin, Jean Shimpton, and Twiggy dominated the fashion industry because of their svelte and youthful appearance. The generation was drawn to not only their look but their child-like joie de vivre. Images of young, slim, white Euro-American women dominated the media from the glossy pages of magazines to the big silver screen.

Contemporary viewpoints on fatphobia, ageism, sexual liberation, and choice are deeply entrenched in the patriarchal system; This brings in the question, 'is the mini skirt a symbol of liberation or patriarchy?' The mini skirt, likened to the contraceptive pill, was originally intended to liberate women through choice and less constricting garments. The origins of the mini skirt started in the 1950s as teenage girls wanted more accessible garments to dance in and broke down confides of previously held traditional sentiments. However, male designers and men usurped the design to shorten the hem to exploit women leading feminists to a standstill. Intention and impact are hard to measure, especially in such a polarizing piece of design that can be seen as centering men for sexually advantageous reasons. However, does this argument negate the presence of women fashion designers and the women who inspired them?

Fashion design is already a male-focused industry. As design historian Cheyl Buckley has stated. "fashion as a design process is thought to transcend sex-specific skills of dexterity, patience, and decorativeness associated with dressmaking."(Made In Patriarchy, 5) This gender divide between fashion designer and dressmaker is seen in the works and history of Quant, Saint Laurent, and Courréges. The former owns a high-end boutique but does not create haute couture, the hallmark of high fashion. Saint Laurent and Corréges were trained by notable fashion houses and made their labels. Due to their name power, the male designers have their names linked to the mini skirts history. Nevertheless, male fashion designers have blurred the true intention of women's desires with their own patriarchal bias. On the other hand, Quant does not want the credit as it takes away from the creativity and agency of the women and girls she drew inspiration from. By allowing the mini skirt to be inherently linked to the male gaze takes away women's autonomy because it strips women of having a choice in their own performance and clothing. Unfortunately, patriarchal codes are ingrained in the fabric of civilization, and at their core are concerns of women's liberation and rebellion.

Mary Quant (British, 1930-2023) Eclair Dress (1969) V&A

The 1960s redefined a generation on the precipice of burgeoning sexuality. Through new technology, popular culture, and design- the social traces of the Women's Liberation Movement challenged pre-existing codes of feminine performance. By politicizing the hemline of skirts, the world centered feminist discourse and reevaluated women's socio-political role in the urban sphere. Whether or not the mini skirt opposed the patriarchy in a world coming to terms with women's liberation and sexual autonomy, the design made people evaluate the ramifications of fashion, consumerism, and feminism. Although the concrete intention and impact of the mini skirt are contested, the garment stands as a symbol of globalized fashion that helped solidify young British women's identity. But in the globalized system of fashion, where does that place the rest of us? I guess that can be left up to choice.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Bell, Melanie. “Young, Single, Disillusioned: The Screen Heroine in 1960s British Cinema.” The

Yearbook of English Studies 42 (2012): 79–96.

Bruley, Sue. “‘It Didn’t Just Come out of Nowhere Did It?’: The Origins of the Women’s

Liberation Movement in 1960s Britain.” Oral History 45, no. 1 (2017): 67–78.

Buckley, Cheryl. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.”

Design Issues 3, no. 2 (1986): 3–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1511480

Cook, Hera. “The English Sexual Revolution: Technology and Social Change.” History

Workshop Journal, no. 59 (2005): 109–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472788.

Conekin, Becky E. “Eugene Vernier and ‘Vogue’ Models in Early ‘Swinging London’: Creating

the Fashionable Look of the 1960s.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 41, no. 1/2 (2012):

89–107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23611773.

Gregory, Georgina. "Go-Go Dancing – Femininity, Individualism and Anxiety in the 1960s."

Film, Fashion & Consumption 7, no. 2 (2018): 165-178. https://login.libproxy.newschool.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/go-dancing-femininity-individualism-anxiety-1960s/docview/2199058244/se-2?accountid=12261.

Hillman, Betty Luther. “‘The Clothes I Wear Help Me to Know My Own Power’: The Politics of

Gender in the Era of Women’s Liberation.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 34,

no. 2 (2013): 155–85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5250/fronjwomestud.34.2.0155

Jones, Peter. A Class Act: Mary Quant and Terence Conran in the Long Sixties, The Sixties,

13:2, (2020): 156-159, https://doi.org/10.1080/17541328.2020.1749460

Marwick, Arthur. The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United

States, c. 1958-c. 1974. Oxford: Oxford University Press, (1998). Print.

Paoletti, Jo B. “Feminism and Femininity.” In Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the

Sexual Revolution, 35–58. Indiana University Press, 2015.

Prisco, Dorothy D. “From Neckties to Blue Jeans: Student Dress and Social Change.” Studies in

Popular Culture 4 (1981): 49–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45018076.

Van Reij, Frederique. “Wearing Mondrian Yves Saint Laurent’s Translation from High Art to

Haute Couture.” The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 60, no. 4 (2012): 342–59.

Vettel-Becker, Patricia. “Space and the Single Girl: Star Trek, Aesthetics, and 1960s Femininity.”

Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 35, no. 2 (2014): 143–78.

Коментарі