Mulher Cosmopolita: José Carlos, Para Todos, and Birth of Brazilian Modernism

- TJ Moss

- Aug 5, 2023

- 8 min read

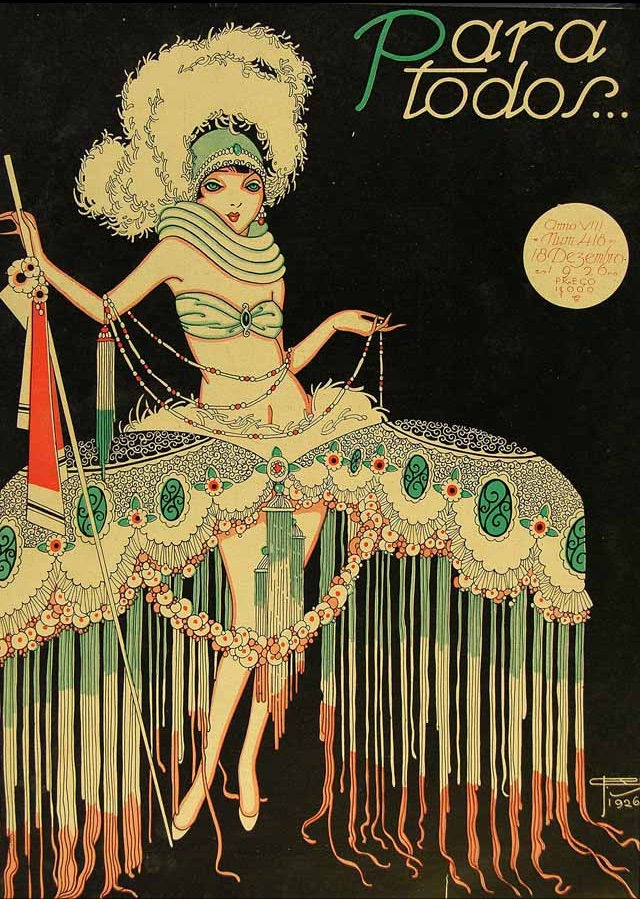

José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Cover for Para Todos (December 1926)

When you think about Brazilian art, who comes to mind? Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973), Anita Malfatti (1889-1964), and even Antonio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994) are all fundamental to the canon, but it does seem that, unfortunately, Brazilian artists still have yet to break into the art historical canon to a sufficient amount. Within the overtly overrepresented practitioners of art, we find primarily affluent white men who were well-bred and studied to become some of the best academicians in the world. Despite academic art having its place and time, it is the avant-garde that is truly favored today for its ability to push the needle forward and declare power in the hands of the (usually) marginalized. However, despite the penchant for vanguard taste, many savants still need to actively pay attention to the importance of Latin American modernists when discussing twentieth-century modernism. Everyone looks toward the major metropoles: Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and New York, but these discourses disengage with the ‘periphery’: Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Middle America. While Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) and Diego Riviera (1886-1957) may be household names, and people may recognize a José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) mural from time to time, it is still apparent that Mexican muralism is one of the only forms of Latin American arts that have breached the “sacred” canon. To the untrained eye, it can seem that modernism only existed in the Occidental West. However, due to colonialism, slavery, and global trade- cosmopolitan centers and modernism affected every part of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century life.

Brasiliana Fotográfica

This particular story starts in Brazil- Rio De Janeiro, to be specific. In the ending days of the Empire of Brazil, the capital was ablaze with discussions on political debates on the abolition of slavery. Since the 1530s, northern Brazil had been a hotbed for sugarcane, and Brazilian plantation slavery, also known as Fazendas ran rampant throughout the country. Enslavement of the indigenous and imported population would only worsen throughout the centuries, especially when the coffee bean was introduced in the eighteenth century. Despite gaining independence from Portugal in 1822, Brazil was still under the imperial rule of Pedro 1 of Brazil (1798-1934) and Emperor Pedro II (1825-1891). In 1888, while Pedro II was recovering from a medical condition in Milan, slavery was abolished. In toe, a wave of Republicanism swept the nation by the wealthy plantation owners who called for the abdication of Pedro II. A Coup d’etat overthrew the monarchy the following year and sent the last Imperial family into exile.

Fig 1: Simplício Rodrigues de Sá (Portuguese, 1785–1839) Portrait of Pedro I of Brazil (c. 1830) oil on canvas. Museu Imperial de Petrópolis.

Fig 2: François-René Moreaux (French, 1807-1860) Family portrait of Emperor Pedro II, with his wife Teresa Christina and their daughters, princesses Isabel and Leopoldina (1857). Oil on Panel. Museu Imperial de Petrópolis.

Fig 3: Sugar-Can Plantation (19th Century)

What resulted was the First Republic of Brazil, also known as the Old Republic (1889-1930). Despite lasting over forty years, Brazil’s government and civilians were disparate on many significant issues, including the importance of cosmopolitanism. It is important to note here that although it was a republic, the country was indeed run by the wealthy landowners of the north. This oligarchy wanted heavily to dispose of its traditional past and ‘join’ the Western world. In 1922, Brazil held the Exposição Internacional do Centenário da Independência do Brasil (International Exposition of the Centennial of the Independence of Brazil) to showcase their economic and innovative prowess on the global stage. The Exposition’s decadence hit a dissonant chord with the civilians of Brazil, especially those living in the south, where the new industry was bubbling up. While the International Exposition was held in Rio De Janeiro, artists from Sao Paulo in the southern tier decided to have their fair, Semana de Arte Moderna (Week of Modern Art), held from February 10th through February 17th, 1922. Often regarded as the start of Brazilian modernism, this art festival brought together visual artists, writers, architects, and composers to showcase their work and push forward new ideas about art, Latin America, primitivism, provincialism, and where Brazil stands within the global scale.

Emiliano de Cavalcanti (Brazilian, 1897-1976) Cover for the Exhibition Catalog for Semana de Arte Moderna (1922) Institute of Brazilian Studies.

According to the scholar of Latin American studies, Edith Wolfe, “The Brazilian modernist saw Paris not as a center to be emulated… but as one of many global peripheries constituting a Brazil-centered universe, where artists went to reclaim images and material expropriated in the colonial process.” (Paris As Periphery, 98) Brazilian modernists’ interest in their heritage and hegemonic power contrasted the Republic’s thoughts on art and design and how they wanted to become Paris. But not even Paris wanted to be Paris during the Années folles (1922-1929). Parisian modernists were interested in the primitivism of Africa, Oceania, Asia, and Latin America to escape the horrors of cosmopolitanism that brought forth the First World War (1914-1919). This tumultuous time that bred European modernism directly results from the traumas of modernity and its weapons. The subsequent style du jour, Art Deco, which developed from the Exposition Universelle de Art Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (1925), retained many essential facets of the ‘peripheries’ artistic ideologies, such as geometric patterning, tribal masks, and luxury materials. So, who is to say that Parisian modernism is more en vogue than anyone else’s?

Jose Carlos de Brito e Cunha at his desk.

José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (1884-1950) was a Brazilian illustrator and graphic designer born in Rio de Janeiro. These categories of art and design went unrepresented at Brazil’s Semana de Arte Moderne. J. Carlos started his career in the arts in 1902 when his illustrations were first published in Tagarela. Over the next five decades, Carlos would have a prolific career in Brazilian graphic design and cartoon illustration, being featured in every significant illustrated periodical of the day. However, the same year as the Semana de Arte Moderne, Carlos took over as head illustrator for the magazine Para Todos (trans: For Everyone), a tawdry film rag before his arrival. Although it stayed the same throughout his work at the magazine, Carlos transformed the cover art and brilliantly displayed Brazilian Art Deco. He found inspiration in European modernist like Erte (1892-1990), American cartoonist like Al Hirshfeld (1903-2003) and even inspired prolific designer such as Walt Disney (1901-1966)

(Fig 1) José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Cover for Para Todos (March 1927)

(Fig 2) José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Cover for Para Todos ( May 1926)

(Fig 3) José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Rua J. Carlos (c. 1940s) ink on paper.

Is Art Deco modern? With its clean lines, industrial aesthetic, and emphasis on social improvement, many would say yes without thinking. But look at Carlos’ covers and know that many Brazilian modernists did not share similar sentiments. Throughout the 1920s, there was a massive shift in how Brazilians wanted to be seen on a global scale. They tried to take back the ‘noble savage’ tropes so that both Europeans and the Republic could not hold power over them quite as easily any longer. Works such as Tarsila do Amaral’s Abaporu, quite literally the Man Who Eats Human Flesh (1928), and the publication of The Manifesto Antropófago (1928) by Oswald de Andrade showcases this temperament in Brazilian arts. De Amaral and Andrade were married; therefore, their artistic license shares similar notions of rejecting modernity to dismiss Republican rule in Brazil. Using primitivism was a mainstay principle of Brazilian modernism as artists and creatives were living in the backlash of the Republic, who took strides to create a hegemonic European class to outweigh indigenous voices. By actively recruiting Europeans to come to Brazil after the abolition of slavery, the First Republic tried to ensure that Brazil would never belong to the real Brazilians. However, who decides what modern can look like? If a Brazilian artist takes inspiration from the periodicals of Paris, and Parisian artists take inspiration from Brazilian art before the colonial period, how are these two art forms different?

Tarsila do Amaral (Brazilian, 1886-1973) Abaporu (1928). Oil on Canvas. 85 cm × 73 cm (33 in × 29 in). Private Collection of Eduardo Costantini

Brazilian Art Deco draws from the French source but utilizes new rediscoveries of indigenous Marajoara designs that employ geometric patterning. The methods signaled to Brazilian modernists and the world over that the land that would become Brazil was very modern and advanced before colonial rule. To quote Wolfe once more,

“Less an expression of anti-colonial resistance, Brazilian modernism was part of a local struggle for national cultural hegemony waged between competing forms of cosmopolitanism, all intrinsically tied to questions of national identity. While academic art reflected Republican ascription to an international community defined as Western civilization, modern art critiqued the neocolonialism of such Eurocentric gestures that, they contended, stigmatized Brazil as provincial and out-of-date.” (‘Paris as Periphery’, 101)

Brazilian modernists were less worried about European colonialism because they were no longer under colonial rule. They despised the Republican government, who wanted to tell them who they were, this being a low-grade form of Paris. But the usurpation of primitivism within Brazilian modernism led to the continual fetishization of Latin American ‘Otherness.’ When Latin American artists utilize their artistic heritage, they are maligned for the usage, but if Europeans like Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) take these same codes, they are genius. J. Carlos utilized these vernacular aesthetic codes mixed with Parisian Art Deco to create these fantastic and wildly understudied magazine covers and illustrations.

Carlos’ oeuvre allows us to recognize what could have been if the colonial discussion did not overshadow the entire Latin American artistic identity. Of course, the ravages of colonialism touch every facet of human nature even today; it is vital to remember that art can be inherently escapist and not overly politicized. We need to remember what real Brazilians were thinking about, seeing, and experiencing during the 1920s as the cracks in the First Republic began to show. We love radical art because it shows us the fight and tenacity within the artist. I want to leave you with this final sentiment: does every art form need to be radicalized and political? And more importantly, can J. Carlos’ work, considered political as its highly imaginative style, rejects the position of the oppressed by emulating European aesthetics perfectly to show that Brazilian artists and designers were just as capable of creating this modern style? This fight between cosmopolitanism and primitivism only further creates the binary that art and design historians are truly so diligently to mend.

(Fig 1) José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Cover for Para Todos (October 1926)

(Fig 2) José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Cover for Para Todos (January 1927)

(Fig 3) José Carlos de Brito e Cunha (Brazilian 1884-1950) Cover for Para Todos (June 1927)

Bibliography and further reading:

Lara, Fernando Luiz. “Modernism Made Vernacular: The Brazilian Case.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 63, no. 1 (2009): 41–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40481001.

López, Kimberle S. “Modernismo and the Ambivalence of the Postcolonial Experience: Cannibalism, Primitivism, and Exoticism in Mário de Andrade’s ‘Macunaíma.’” Luso-Brazilian Review 35, no. 1 (1998): 25–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3514120.

Mitter, Partha. “Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery.” The Art Bulletin 90, no. 4 (2008): 531–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20619633.

Wolfe, Edith. “Paris as Periphery: Vicente Do Rego Monteiro and Brazil’s Discrepant Cosmopolitanism.” The Art Bulletin 96, no. 1 (2014): 98–119. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43947708.

Comments