In Search of Lost Time: Finding Russian Identity in Mir Iskusstva Fairytale Illustrations

- TJ Moss

- Aug 26, 2023

- 8 min read

Alphabet in Pictures (Azbuka v Kartinakh 1904), p. 9, University of Washington Library

Fin de Siècle Russia, a land on the precipice of change scrambling for a national artistic identity with equal footing as the rest of Western Europe. Fatigued of the sobering realism of peredvizhnichestvo propelled young artists in St Petersburg and Moscow, namely Alexandre Benois (1870-1960), Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929), and Lèon Bakst (1866-1924) to formulate a new artistic practice and art journal, Mir Iskusstva; this art movement had two missions according to its members: look at global art to launch Russian fine and decorative arts into the mainstream and to look at Russian folk arts to solidify a national identity away from the “western” ideal. Mixing both contemporary styles of L’Art Nouveau and Aestheticism with Renaissance, Medieval, Japanese Woodcut, and art from the Russian North, Mir Iskusstva reinvigorated Russia infiltrating all forms of art and design. The imbrication of folk and modern practices especially come forward in the works of artist and designer Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942). By exploring his illustrations for Russian and Slavic folk/fairy tales we will see the intersection of fine arts, craft, modernity, and feminism in the grander popular consciousness in Russian graphic design.

Vasily Ivanovich Surikov (Russian 1848 – 1916) The Morning of the Streltsy Execution (1881), Oil on Canvas, 218 cm X 379 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Prior to the formation of Mir Iskusstva, the primary style of peredviznichestvo was meant to show a certain level of objectivity in the Russian arts. The school of artists rejected the “art for art's sake” sentiments of the mid-to-late nineteenth-century after the advent of photography and pictorial realism. Peredviznichestvo artists, in fact, there was an immortality in modern art and held on to more utilitarian ideologies of art production. Art historian Stuart R. Grover has stated that before Mir Iskusstva “the works of Russian artists in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries have been virtually forgotten and the earlier art has been ignored.” (Grover, 35) This neglect of the importance of Russian art and design to Russian National identity was from the incomplete curricula and conception of art historical discourse in the county. The lack of art historical literacy was subjugated by Peter the Great's (1672-1725) westernization of the country in the early-eighteenth century that denied all folk crafts and looked only to Western Europe's art production, especially favoring Dutch Delftware. Anna Winestein, art and theatre historian explains that the Mir Iskusstva “lay[ed] the foundation for the discipline of art history and becam[e] deeply involved in the heritage preservation movement, both before and after the Revolution.” (Winestein, 320)

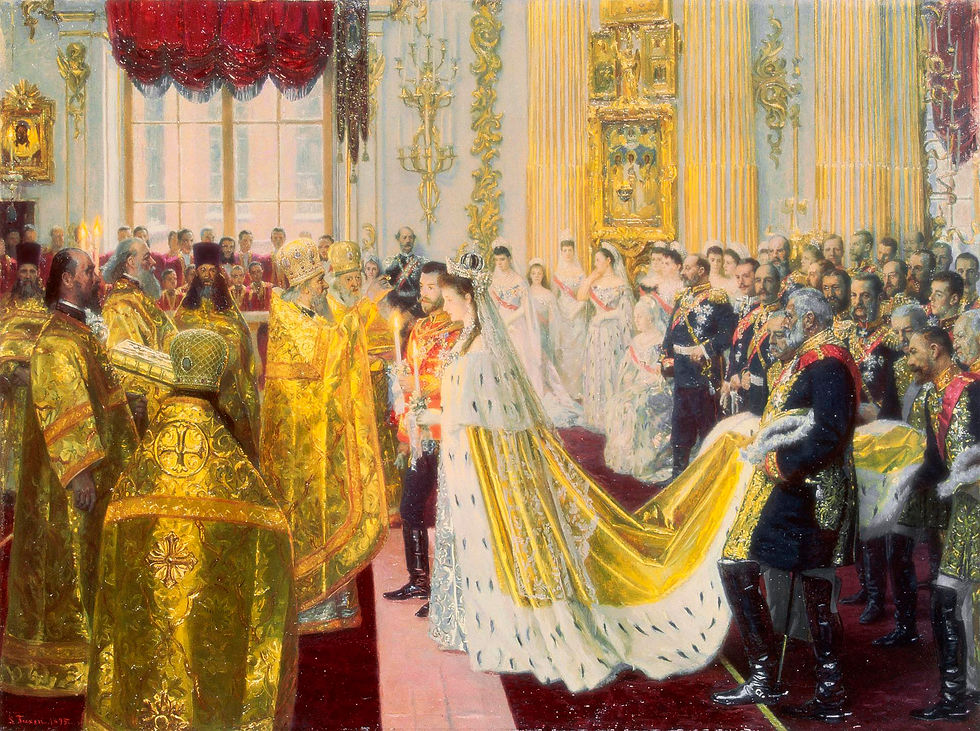

Laurits Regner Tuxen CVO ( Danish, 1853 –1927) The Marriage of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress of Russia, 26th November 1894 (1895). Oil on Canvas. 65.5 cm X 87.5 cm. Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Prior to the revolution, Alla Rosenfeld, Research consultant for the Merrill C. Berman Collection asserts “the idea of Russianness [w]as defined by personal loyalty to the Tsar and faithfulness to the Orthodox Church.” (Rosenfeld 172) This was a reaction against the secular westernization of Peter the Great and therefore the cultural production of his reign was erased from public memory to centralize governmental control of society. Professor of Art History at Indiana University, Janet Kenndy holds that “although Peter the Great's westernization of Russian culture had derailed Russian Art for over a century, forcing Russian artists to observe a ‘universal’ standard of beauty established at the art academies of Western Europe, the heroic Revolt of the Fourteenth in 1863 had broken this stranglehold, making it possible for Russian Artists to choose their own path.”(Kennedy, 144) However, it would still be three decades before the invention of the Mir Iskusstva movement and Journal.

Elena Polenova (Russian, 1850-1898) The Beast (before 1898). Oil on Canvas. 44cm X 103 cm. State Museum Abramtsevo Estate, near Moscow

Although avant garde styles and artists arose in Russian art throughout the nineteenth century, there was no avant garde or folk art movement centered in the capital city of St Petersburg. The Abramtsevo Circle, centered in Moscow laid the foundation for what the Mir Iskusstva would do less than a half century later in terms of theme and materiality. Wendy Salmond, scholar of Russian and Early Soviet art, architecture, and design illuminates the similarities; she states “a personal sense of Russian identity could be distilled from one’s intense early memories of place (native flora, fauna, and wildlife) just as generations of peasants has done throughout their crafts” (Salmond, 9). Thus designers of “furniture, embroideries, ceramics, decorative painting, and interiors open[ed] up areas of expression that challenged the rationalism of the western mindset and the realism of adulthood” (Salmond, 8). The importance of Russian rural childhood would become an important factor in the art and design of the country as they continued to define themselves against western hierarchical standards.

Arthur Rackham (British, 1867-1939) The True Sweetheart: “The third time, she wore the star-dress which sparkled at every step.” (1917) Pen and Ink. Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales (Originally Printed 1917)

Arthur Rackham (British, 1867-1939) Snow White and The Seven Dwarfes (1917) Pen and Ink. Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales (Originally Printed 1917)

Arthur Rackham (British, 1867-1939) United (1904) Pen and Ink. University of California Collections.

The conception of morality became highly scrutinized in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, as the Church regained its prominence in society due to Victorian demands of religiosity. Of course, any form of religious text is important to the teachings of the Church, but so was the prevalence of folk and fairy tales of the time which teach children lessons. Around the same time that Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (1785-1863), Wilhelm Carl Grimm (1786-1859), and Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) were transcribing western fairy tales for the masses, Alexander Afansayev (1826-1871) was collecting Russian folklore to be published between 1855-1867. Afansayev had an interest in illustrating the works and would ask a myriad of Russian illustrators to help; most prominently Elena Polenova (1850-1898), a member of the Abramtsevo Circle and the first illustrator of fairy tales in Russia.

Russian and Slavic fairy tales challenge conventions of western tales due to their relatively stronger heroines. Folklorist Kay Stone states that “heroines [from western tales] have their freedom severely restricted at the time in life when heroes are discovering full independence and increased power” (Stone 47) Referencing early Disney heroines written by the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault (1628-1703) such as Snow White (1937), Cinderella (1950), and Aurora (1959). This lack of female agency in fairy tales and Disney films has to do with the time and place of publication and gendered stereotypes in the Euro-American zeitgeist.

Marc Davis (American,1913-2000), Eric Larson (American,1905-1988), and Les Clark (American,1907-1979) Walt Disney’s Cinderella (1950) Cell Animation. The Walt Disney Company.

However folklorist, Jessica Hooker contends with the implications of female agency in eastern European tales by discussing how the fears manifested in female agency when a heroine takes on a traditionally masculine role saying “ [there is and] underlying message that women who take up the sword have two options: be re-domesticated by a husband, or to sacrifice their femininity and become actual men, for in yielding this powerful symbol of masculinity they represent an intolerant threat to male dominance.” (Hooker, 178) These claims of misogyny in fairytales are ever present in a society that has systematically placed women below men for centuries, especially in a patriarchal society defined by the Orthodox Church. However, looking at a small sample size of fairy tales originating from the Slavic region does not define the fate of women in a country's cultural production.

Ivan Bilibin (Russian, 1876-1942) Vasilisa the Beauty at the Hut of Baba Yaga (1899) Applied Graphic Design: Illustration.

The tale, Vasilisa the Beautiful, tells the story of a young girl who receives a doll from her father after the death of her mother. She is told that the doll will keep her from harm's way as long as she never shows it to anyone. The father remarries and his new bride brings two stepdaughters with her, but they are very cruel to her. Unfortunately, Vasilisa is left with her step family after her family goes out of town. The same day, the entire family leaves to a secluded cottage in the woods and Vasilisa is left to do all of the housework and errands for the family. After running into Baba Yaya, a famous slavic folk character, Vasilisa must perform tasks or she will die. The doll keeps her alive and she is allowed to return home with fire. She eventually becomes assistant to the head cloth maker in the Capital. Upon meeting the Tsar, they are either married or she goes to work for him, depending on the telling. This distinction in who is doing the telling is highly important in any folkloric rendition. It is not common for grown heroines to be unwed or having high status employment at the end of their story. The feminist undertones of the text came to be translated to the visual culture associated with the literature.

Boris Mikhaylovich Kustodiev (Russian: 1878 – 1927) Portrait of Ivan Bilibin (1901) Oil on Canvas. Oil on Canvas. Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

Ivan Bilibin, illustrator in the Mir Iskusstva designed works for a reissue of Narodnye Russkie Skazki in 1899. The work of Vasilisa the Beauty at the Hut of Baba Yaga, showcases an admiration to folk style in the border, landscape, and sarafan and poneva worn by the central figure. Although, Mir Iskusstva takes a lot of inspiration from L’Art Nouveau, the illustration of Vasilisa subverts the troupes of Art Nouveau women as “early pin-up girl[s] either [reflecting a personality of] bubbly, carefree, and gay, or terribly seductive”(Thompson, 160), as defined by professor of art history, Jan Thompson. Bilibin was more interested in the “extensive use of motifs from Luloki, early Russian illuminated manuscripts, peasant embroideries, and carved and painted wooden utensils.” (Rosenfeld, 180). Bilibin’s constructed illustrations formulate the basis for Russian national identity as defined by the folk traditions already in the country, yet ignored, by going to the Russian North and learning from those folk communities. “Miriskusniki reinterpreted the meaning and appearance of Russian-ness by simplifying their sources and fusing them with European and Asian ones to transcend the revivalism inherent to the style Russe developed within the design profession.” (Winestein, 319)

Ivan Bilibin (Russian, 1876-1942) Sadko (1902) Applied Graphic Design: Illustration. From The Fairytale The White Duck

Ivan Bilibin (Russian, 1876-1942) Tsar Dadon meets the Shemakha Tsarevna(1906) Applied Graphic Design: Illustration. From The Fairytale The Little Golden Cockerel

Ivan Bilibin (Russian, 1876-1942)The Island of Buyan (1905) Applied Graphic Design: Illustration. From The Fairytale The Tale of Tsar Saltan

By challenging the understanding of Russian realism, the artists associated with Mir Iskusstva redefined artistic provenance and national identity in Russia prior to the revolution. Hoping to find an art historical discourse to unite and educate the civilians of Russia, the Avant Garde could not predict that unification was too far gone and soon Russian craft would be replaced by constructivist sentiments as socialism weaved itself into the fabric of Russian identity. For the sake of historiography, this period is significant in the production, cultivation, and publication of Russian art and design that continues to stay relevant today. It makes you think, what would have happened if the Tsars had commissioned artists in the Mir Iskusstva instead of ostentatious Faberge to define royal splendor and national opulence.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Grover, Stuart R. “The World of Art Movement in Russia.” The Russian Review 32, no. 1 (1973):

Hooker, Jessica. “The Hen Who Sang: Swordbearing Women in Eastern European Fairytales.”

Folklore 101, no. 2 (1990): 178–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1260321.

Kennedy, Janet. “Closing the Books on Peredvizhnichestvo: Mir Iskusstva’s Long Farewell

to Russian Realism.” In From Realism to the Silver Age: New Studies in Russian Artistic

Culture, edited by Rosalind P. Blakesley and Margaret Samu, 141–51. Cornell University

Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv177t9k1.15.

Polyakov, L. V. “Women’s Emancipation and the Theology of Sex in Nineteenth-Century

Russia.” Philosophy East and West 42, no. 2 (1992): 297–308.

Salmond, Wendy. “The Russian Avant-Garde of the 1890s: The Abramtsevo Circle.” The

Journal of the Walters Art Museum 60/61 (2002): 7–13.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20168612. Rosenfeld, Alla. “Between East and West: The Search for National Identity in Russian Illustrated

Children’s Books, 1800-1917.” In From Realism to the Silver Age: New Studies in

Russian Artistic Culture, edited by Rosalind P. Blakesley and Margaret Samu, 168–88.

Cornell University Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv177t9k1.17.

Stone, Kay. “Things Walt Disney Never Told Us.” The Journal of American Folklore 88, no. 347

(1975): 42–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/539184.

Thompson, Jan. “The Role of Women in the Iconography of Art Nouveau.” Art Journal 31, no. 2

(1971): 158–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/775570

Winestein, Anna. “Quiet Revolutionaries: The ‘Mir Iskusstva’ Movement and Russian Design.”

Journal of Design History 21, no. 4 (2008): 315–33.

Comments